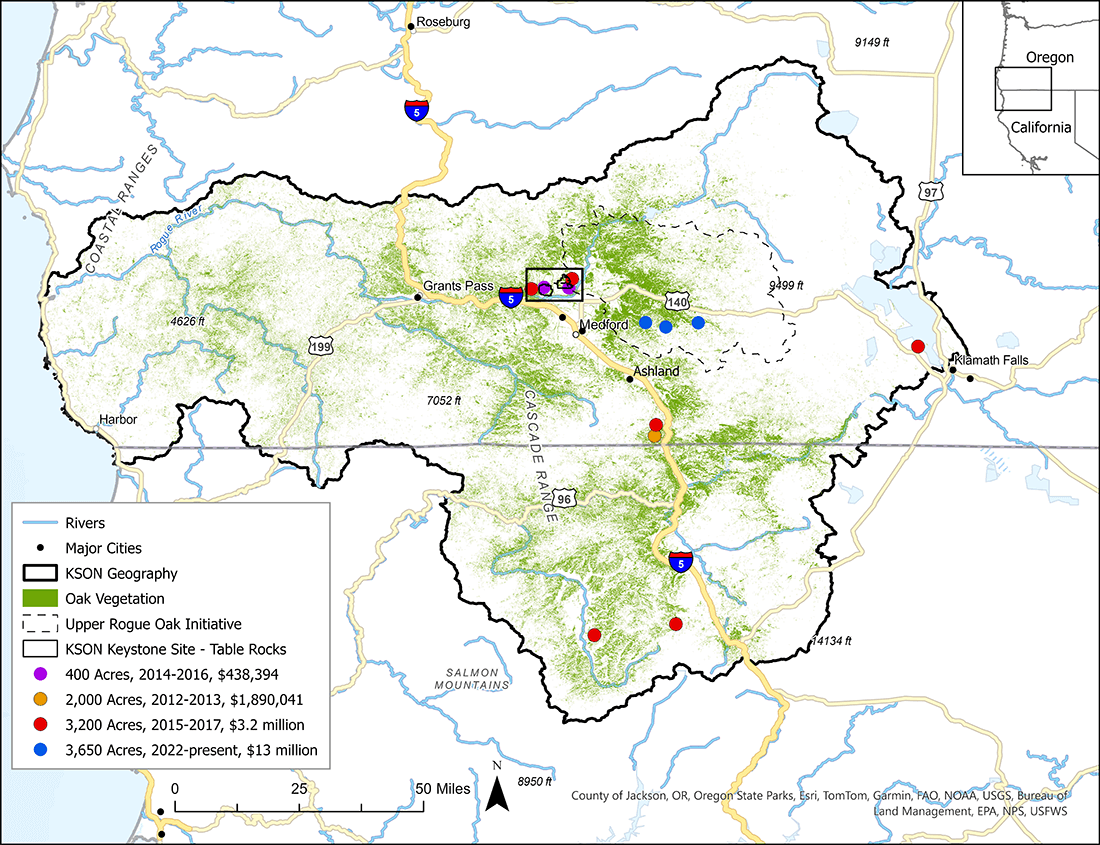

Our Region

Klamath Siskiyou oak Photo credit: Jaime Stephens

The Klamath Siskiyou Oak Network geography contains some of the most extensive remaining oak ecosystems in the western United States. It boasts high biodiversity and endemism as part of the Klamath-Siskiyou Bioregion, a globally significant biodiversity hotspot and area of conservation concern. It serves as an important climate refugium and area of connectivity between Oregon and California.

Historically, oak trees were widespread throughout the valleys and foothills of Oregon, California, and Washington. Since the start of European settlement in the mid-1800s, Oregon has experienced significant losses in oak habitat, with estimates ranging from 50% to near-total loss. Moreover, many of the remaining oak habitats in Oregon are found on poorer soils, as more productive lands have been largely cleared for other uses. California has also lost 33% of its oak woodlands, and Washington faces similar habitat loss challenges.

A variety of factors have contributed to the loss of oak habitats. For time immemorial, the oak ecosystems of this geography have been stewarded by Indigenous peoples.

Tribes have a deep cultural knowledge of oak woodlands, and regard the plants, animals, natural resources, and even natural processes as relations. These relations include a cultural stewardship approach to managing for beneficial uses of traditional resources including oaks, acorns, fire, oak-associated subsistence first foods, and many other oak-associated species. Over time, Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated traditional practices that shaped landscapes to support sustainable foraging, gathering, and hunting for ceremonial and subsistence purposes. Some traditional benefits of managed oak habitats included food and fiber resources such as acorns, bulbs, deer meat, and regalia, as well as aesthetic benefits and community protection from severe fire.

Fire has long been an indispensable tool for Indigenous peoples in stewarding landscapes. Many tribes with ancestral lands in Oregon and California have evolved fire-dependent cultures and continue to use fire to this day. They rely on cultural burning to increase the quality and quantity of plants, limit pests, enhance germination or re-sprouting, and promote desirable forms of growth. As a reflection of their value to Indigenous communities, ancestral village sites are often located near oak woodland habitats.

Following European settlement, many oak woodlands and savannas were converted for agriculture or urban development. Also, decades of fire suppression during the latter half of the 1900s has allowed less fire-resistant, yet faster-growing tree species, such as Douglas-fir, to encroach upon and displace oak trees. In the case of pasture conversion, cattle grazing can degrade oak systems by compacting soils and reducing oak regeneration. More recently, non-native invasive species — including plants, insects, and disease agents — have contributed to negative impacts in oak habitats. For example, the invasive shrub Scotch broom has altered understory and shrub communities in these habitats, and the disease Sudden Oak Death has devastated some oak forests in California and Oregon.

The degradation and loss of oak habitats has led to real and negative consequences for wildlife.

Almost half of the 49 bird species in the Pacific Northwest that are highly associated with prairie-oak habitats have experienced extirpations, range contractions, and/or regional population declines. This habitat decline has affected other wildlife too, including mammals, butterflies, and other invertebrates. Fortunately, wildlife populations can usually bounce back if

appropriate habitat conditions are in place for wildlife to live and breed.

Even with loss and degradation, the oak ecosystems here are among the most biodiverse in the Pacific Northwest. They host many endemic plants and over 300 vertebrate species, including a high diversity of oak-associated birds, many of which are of continental conservation concern. For time immemorial and continuing today, these oak ecosystems have provided and continue to provide culturally important plants and resources that sustain Indigenous communities.